Images of America: St. Augustine Florida

By Maggi Smith Hall

Published by Arcadia Press, Mt. Pleasant SC

Introduction – The development of image copying to document St. Augustine

The first known visual images of the land we now call Northeast Florida were created in 1564-1565 by Jacques Le Moyne, a French artist who accompanied Jean Ribault and Rene de Laudonniere on their voyage to the New World. Their ill-fated settlement, Fort Caroline, located at the mouth of the present-day St. Johns River near Jacksonville, lasted but a few years. However, Le Moyne’s 42 drawings of the aborigines he met offer a remarkable and detailed account of life in La Florida before the impact of European migration.

At a time that seems primitive by modern standards, visual image-makers had been reproducing their likenesses, the images of their shelters, food, clothing, and natural surrounds for eons. They drew, painted, and carved in the dark recesses of caves, inside the labyrinths of pyramids, on papyrus, and on cliffs so lofty that contemporary man gazes in astonishment at their creative tenacity. They ingeniously used whatever materials nature afforded—charcoal, stone, metal, graphite, berry and bark juice, sand, and clay.

As time marched forward, image-makers explored new ways to record visual forms. By 350 B.C., during the time of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, they were experimenting with visual capturing or duplicating their surroundings on some type of material using a device based on the function of today’s camera. This invention, eventually perfected in the early 1500s by Leonardo da Vinci, was named a camera obscura or “dark chamber.”

Although the camera obscura was in existence during the time that the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon discovered the Florida peninsula in April 1513, he did not have access to such a device; neither did he have an artist accompanying him, as did Ribault. It would be de Leon’s naming of his discovery and his descriptive words that allowed Europeans to see mentally or “picture” his discovery. He named this land “La Pasqua de Florida” – Pasqua for “Easter” and La Florida for “The Flowery Land.” He explained his choice thus: “because it was very pretty to behold with many refreshing trees.”

A year after Ribault’s settlement was founded, Spain’s King Phillip II commissioned Pedro Menendez de Aviles to “explore and colonize La Florida,” driving out settlers not subject to the Crown. By September 1565, Menéndez and hundreds of soldiers and settlers were sailing north along the coast of La Florida. Sighting a protected bay teeming with dolphins, Menendez and his crew disembarked near the Timucuan Indian village of Seloy. He ordered a Spanish flag and cross to be placed in the sand, boldly proclaiming this land for his king. In honor of the Catholic Saint Augustine, Menendez named his new settlement San Agustin.

As life in San Agustin moved arduously forward, little attempt was made to record visually the images of this military outpost. Life during that first Spanish period (1565-1763) was too difficult to indulge in frivolous tasks such as drawing or painting. However, in Europe, image-makers persistently worked to improve the camera obscura.

By 1763, continued European conflict eventuated in La Florida being transferred to England. The image of this shift in ownership was recorded with pen and ink. In 1783, Florida was returned to Spain. However, by the early 1820’s, the new upstart country, the United States of America, was aggressively pursuing Spain’s evacuation of its wilderness peninsula. In 1821, given an offer it could not refuse, Spain reluctantly agreed for the United States to pay Spain’s international debts totaling $5 million in return for La Florida. On July 10, 1821, La Florida became a United States territory.

Although no American dabbled with inventing a mechanical image-making device, Europeans remained hard at work with their camera obscura, while events in America and St. Augustine continued to be documented visually with pen, ink, paints, paper, and canvas.

Five years after Florida became part of the United States, Joseph Niepce, a Frenchman, successfully achieved a way to generate mechanically the eye’s image and to make those images permanent. Niepce’s procedure, called heliograph (from the Greek word helios for “sun” and graphos for “drawing”), captured images on a sheet of pewter. There remained a significant drawback with his process however—exposure time was eight hours. Since no one wanted to sit for a photographic session of such length, his picture taking entailed only fixed objects and scenery.

Niepce’s invention peaked the curiosity of another Frenchman, Louis Daguerre, who had been experimenting with the diorama or panorama scenes re-created with the camera obscura, translucent paintings, and special lighting. After years of experimentation, Daguerre’s new process of images captured on metal plates reduced exposure time from eight hours to thirty minutes. He also discovered that an image could be permanent by immersing it in salt.

In January 1839, Daguerre announced his discovery, the daguerreotype, to the French Academy of Sciences. A French newspaper enthusiastically reported on his astounding image-capturing process: “What fineness in the strokes! What knowledge of chiaroscuro! What delicacy! What exquisite finish! How admirably are the foreshortenings given—this is Nature itself!”

Not everyone received the news of Daguerre’s success with enthusiasm. The Leipzig City Advertiser criticized: “The wish to capture…reflections is not only impossible…but the mere desire alone, the will to do so, is blasphemy. God created man in His own image, and no manmade machine may fix the image of God. Is it possible that God should have abandoned his eternal principles and allowed a Frenchman…to give to the world an invention of the Devil?” Perhaps it was technological envy that provoked the German opinion—especially given that it was the French who bested them—or perhaps it was simply the fear expressed by some artists that Daguerre’s technique would negatively affect their profession. In any case, the fact remains that the centuries-old endeavor to capture an image permanently had been achieved. Although Daguerre’s technique was an expensive once-only process, it encouraged continued improvements for a “manmade machine…[to] fix the image of God.”

That same year, 1819, Englishman Sir John Herschel coined the word “photography,” derived from the Greek words photos, meaning “light.” And graphien, meaning “to draw.” This new word was later used to describe all processes by which the eye’s image was mechanically reduced and images were captured on paper, rather than on glass or tin. Many felt the images were inferior to the daguerreotype. Indeed, by 1853, they were so immensely popular in America that an estimated three million daguerreotypes were produced annually.

A new process refined in 1851, called the collodion wet-plate, combined the best of the calotype with the best of the daguerreotype. Although the equipment was cumbersome, it increased image-making. Due to the new technique, photographers hailed a carriage or a train to travel the continent, taking their artistic talent into small communities to freeze—on glass or on tin—faces and landscapes.

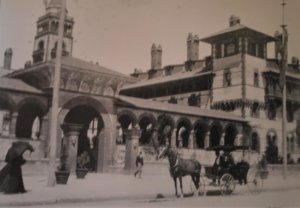

Horse hooves and carriage wheels clamored along the Florida corduroy road leading from Picolata on the St. Johns River to St. Augustine. Photographic equipment bounced precariously atop the coach. Passengers coughed, their eyes teared from dust churning through uncovered windows, but stalwart hearts beckoned them on. They were convinced that the 18-mile trip from the steamboat dock to the nation’s oldest city would be worth the inconvenience. After all, since 1821 newspapers and magazines had praised the virtues of visiting the United States’ newest territory and especially its eastern capital, St. Augustine.

Then, after 100 years of people coming to town, the camera finally arrived.